How do stories create leverage?

Everyone says it’s essential to be a good storyteller. Here’s the reason why.

Whether you work in a creative industry where stories are the product or in a tertiary industry where they help sell the product, storytelling's importance is rarely questioned.

But press someone on why storytelling works across so many contexts, or ask what fundamentally makes stories valuable, and you’re likely to hit a dead end.

This article takes a different approach, moving past vague explanations to explore the precise elements that make stories a powerful force multiplier.

Let’s dive into why stories are valuable and how they create leverage.

Talking points in today’s post

Stories & leverage: How stories leverage ideas to overcome natural barriers of space and time

The abstract & concrete: How stories achieve scale and longevity by combining the concrete and the abstract

Shifting from outsider to vicarious participant: How stories morph perspective to bring outsiders in.

Why is everyone telling you to become a storyteller?

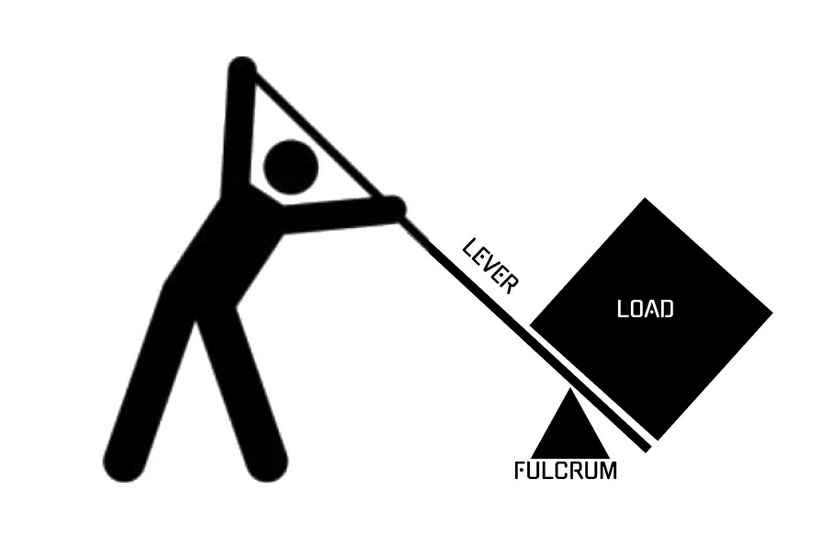

“Leverage squeezes the full potential out of something with less effort. Stories leverage ideas in the same way that debt leverages assets.”

Morgan Housel, Same as Ever

Put simply, ‘leverage’ is the power that allows you to get more out (output) for what you put in (input).

In communications, your input is everything from your initial idea, raw information, the time it takes to research and write, word count, filming etc. Two main things will determine what you get back (output). But to understand them, we must first look at the two main barriers which strip your ideas of leverage:

Space: The physical distance between people. This makes large numbers of people hard to reach, and even when a large audience is gained, it’s difficult to deliver a message that resonates with them, all of whom have different frames of reference and experiences.

Time: Everything that passes through time eventually decays, and ideas and information are no different. Both have a short shelf life.

Stories & communication technologies - moving through space and time

When overcoming these two barriers, storytelling isn’t the only force amplifier. Communication technologies—from human language to algorithms—set major parameters on how your information travels across space and time.

Communication technologies determine who you can reach, where and when you can reach them, and at what scale.

Storytelling, on the other hand, focuses on shaping your ideas to create a desired emotional impact—one that resonates at scale and endures over time.

Communication technologies might be able to reach a million people, but that doesn’t mean the message will resonate with them in the same way or that the information will be remembered.

Stories bridge the gap between people with vastly different experiences and geographies (space) while embedding ideas and information into something enduring—the human memory (time).

Scale - how stories overcome space

The cognitive evolution

Around 70,000 years ago, the Cognitive Revolution enabled Homo sapiens to think in abstract terms and communicate about things that do not exist in the physical world, such as gods, nations, laws, and money.

In ‘Sapiens, A Brief History of Humankind’, Yuval Noah Harai emphasises how being able to think in abstract terms gave birth to storytelling, allowing Homo sapiens to transcend the ‘Dunbar's number’ limit of 150 stable relationships in a social group.

Evolution of communication technologies

Over time, technology has also evolved so that stories can be distributed on a larger and larger scale, starting with the invention of human language, writing systems (hieroglyphs and alphabet), the printing press, the telegraph, radio, film, TV, and the internet.

The Meme - ideas that spread virally

While stories have evolved so that messages can resonate on a larger and larger scale, there’s also research to suggest that good stories can amplify reach in and of themselves.

Richard Dawkins's idea of the ‘meme’ is an idea, behaviour or style that spreads using imitation from person to person within a culture and often carries symbolic meaning. Those who support this theory see memes as the cultural equivalent to genes in that they self-replicate, mutate and are also beholden to natural selection.

Longevity - the power of stories that endure over time

The earliest communication systems were designed to extend the life of ideas and information beyond human memory. In the Neolithic period (around the 7th millennium BCE), proto-writing systems used demographic or mnemonic symbols to convey limited information. These systems predated formal writing and ensured that ideas could outlive individual recollection.

Stories take this concept further by extending the lifespan of ideas and, in some cases, granting them immortality. This makes storytelling an invaluable tool for several reasons:

Brands need time to create enduring value

Like the symbols of ancient civilizations, brands act as a kind of corporate hieroglyph—a symbolic shorthand for a company’s promise and value. In Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy, branding is identified as the fifth power, offering businesses a long-term advantage. The associated barrier, which prevents competitors from replicating this advantage, is the time it takes to build awareness and a positive association with a brand. In this context, storytelling becomes a superpower, embedding brand ideas into human memory structures and shaping perception over time.

Old and Ancient ideas are powerful

Certain ideas transcend human memory, enduring over centuries. A look at the history of storytelling reveals a ledger of humanity’s most powerful memes, ideas and concepts. Religions, for instance, are intergenerational stories that have persisted for millennia.

Even outside of religion, there are examples of enduring intergenerational narratives. David Foster Wallace’s claim that “there is no such thing as atheism” suggests that other intergenerational stories—freedom, democracy, law and order—also serve as collective myths or pseudo-belief systems. On an individual level, concepts like beauty, money, power, and knowledge also function as personal narratives, passed down and evolving across generations.

“On one level, we all know this stuff already - it’s been codified as myths, proverbs, cliches, bromides, epigrams, parables: the skeleton of every great story.”

David Foster Wallace, This is Water, on finding things outside religion to worship

Using the abstract to elevate the concrete

So why can stories translate at such a large scale and for such a long time? The answer is in the nucleus of all stories, which uses the abstract and timeless to leverage the concrete and temporary.

Abstract - existing in thought or as an idea but not having a physical or concrete existence. A lot of the time, these come downstream from the most ancient ideas, archetypes and memes

Concrete - existing in a material or physical form, not abstract. While the concrete offers more specificity, these ideas have a shorter shelf life and less ability to resonate with someone on an emotional level and stay in their memory for a long time

The definitions above are antonyms and represent opposite ends of the spectrum regarding communication. Concrete things usually can only be communicated to a smaller and more specific audience. For example, in a business context, if I communicate 1 to 1, I might get into more granular details of a specific product while tailoring this information to the person I’m speaking to.

The opposite is abstract. These can be symbols, images, or analogies - any way something concrete can be packaged to make it possible to communicate in ‘1 to many situations’. In business, the granular and concrete details that work 1 to 1 don’t translate at scale - so in their place, we have some form of sensory shorthand - the brand.

Stories, then, use the abstract to elevate the concrete, making:

Temporary ideas last a lifetime

1 to 1 communications suitable for 1 to many communications

Specific ideas universal

Objective spectating a vicarious experience

Unknown worlds familiar

In fiction

When I watch Peaky Blinders, I have no lived experience in their world. I wasn’t alive in 1919 or involved with crime groups from the midlands. So why do I, and the millions of other viewers, find the series so engaging?

I may not have ever been a member of a Birmingham gang during the 20th Century, but I understand what it’s like to have brothers, to be part of a family, to feel fear, etc.

The genre will also leverage any pre-existing association I have with the crime family genre, with a lot of the characters being iterations of a long narrative lineage of crime family archetypes. For example, when I see Arthur Shelby, in some fundamental way, he harkens back to a long lineage of characters like Christopher from The Sopranos or Sonny from The Godfather.

Good stories combine abstract, emotional core human ideas (family, betrayal, crime, law and justice), enduring narrative trends (the crime family, character archetypes etc) with new, fresh concrete specifics. It’s no coincidence that so many HBO dramas use family (the abstract) as a central theme in Succession, The Sopranos, and Mad Men to give viewers a gateway into different worlds, whether it be the media elite, the mafia, or 1960s advertising (the concrete).

Every story comes with its unknown world for which you don’t have an existing understanding. Storytelling acts as a gateway or passport into the unknown. This allows two utterly different audience members with different experiences in different places to have the same reaction. In the Peaky Blinders example, the story works because Snoop Dogg and I have the same emotional reaction.

“The most amazing thing for me is that every single person who sees a movie brings a whole set of unique experiences. Now, through careful manipulation and good storytelling, you can get everybody to clap at the same time, to laugh at the same time and to be afraid at the same time.”

Steven Spielberg

Shifting from objective to personal

Stories use the universal as a gateway to the specific. But there’s something even more nuanced at play that makes them so powerful.

When people engage with characters in stories, they constantly shift between two states:

1. Outsider Looking In

This perspective is like peering through the wrong end of a telescope—everything feels distant, even if it’s close at hand. In this state, the audience becomes a detached observer, viewing events with little emotional engagement. Bad storytelling often falls into this trap: too many concrete specifics, not enough abstract, universal resonance. The result? A story that struggles to connect.

2. Vicarious Participant

Flip the telescope, and the audience feels closer—even if the story is set a world away, geographically or experientially. In this state, viewers don’t just observe; they feel. They step into the characters’ shoes, experiencing emotions and events as if they were their own. At its best, storytelling creates this vicarious connection, making countless people feel the same thing at the same time. This is where stories become most personal and powerful, uniting diverse audiences through shared emotion.

Thank you for reading!

Stories have the unique power to transcend space and time, embedding ideas into the human memory and shaping how we connect with the world.

They combine the universal and the specific, bridging the gaps between diverse experiences while amplifying emotional resonance. Whether through brands, intergenerational narratives, or the vicarious participation they inspire, stories are more than tools—they are force multipliers that give ideas longevity, scale, and impact. By mastering the art of storytelling, you can reach your audience and leave an enduring mark.